Things you can do with Woodblocks (1)

Welcome to a new series entitled, “Things you can do with woodblocks.” The purpose of this series is to begin outlining some of the special features of xylographic printing with useful visuals.

Black blocks

Until the 19th century invention of different forms of plate printing (stereotype, elecotrotype), it was rather difficult to keep type “standing.” ABCs for Book Collectors explains ‘standing type’ to mean:

The type from which a book was printed was not always distributed immediately after use. It was sometimes kept and used for a subsequent impression, which is then said to be printed from standing type. (209)

Printers only kept standing type in rare circumstances. For most jobs, when printing was done, type would be redistributed to type-cases to wait for the next project.

Xylographically printed books, on the other hand, lasted far longer. If blocks were properly cared for, you could use them for a few generations (with occasional repairs). This also meant that the same blocks could be used for new ‘editions.’ (Edition is a problematic concept in this case, but we’ll talk about this later)

We can see what this means in practice by beginning with something simple. Sometime in 1554/55, officials in the Nanjing Board of Punishments (the legal ministry of the Ming(1368-1644)) compiled an administrative handbook to their office entitled, A Gazetteer to the Board of Punishment[Nanjing Xingbu zhi 南京刑部志]. This book, which contains all of the rules for the office, a historical introduction, as well as personnel rosters, was designed to incorporate updates. Looking at the image below we can see how this worked:

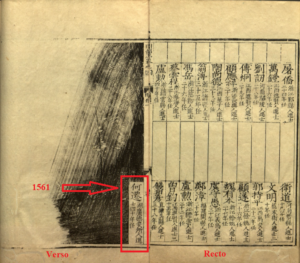

In this image, the recto side of the block (as single side of a block was used to print the recto and verso of a page bound in the ‘thread-bound 線裝’ style) has been completely carved with the names of officials and their dates of service. If we look at the verso side, however, we see only one entry for an official who served in 1561 as well as a large bit of black.

Now, if you remember what I said above, you’ll realize that this gives us something of a problem. The book was printed in 1554/55, or at least that’s how we date based on the prefaces. But here we have an entry from 1561. That’s because the black space is more than an error. It’s uncarved block that has been held in reserve for updated information! If you look closely at the top pf the verso page you can see that a new column has already been lightly carved into the block.

This type of printing flexibility leads to occasional headaches for bibliographers. A good example of this is a text held in the Harvard-Yenching Library. Memorials Left in the Censorate From the August Ming [Huangming liutai zouyi 皇明留臺奏議] was first printed in 1605. This collection of memorials to the throne was allegedly made from the records of the censorate. It was specifically supposed to represent opinions that had been repressed because they had never been forwarded for imperial review. The problem with this text is that it exists in two states. One has only two prefaces, both dated 1605. This is the version photographically reprinted in the Sikuquanshu cunmu. The edition at Harvard, on the other hand, has a third preface, dated 1607. This led Shen Jin to conclude in his catalog of the Harvard collection that there were two editions from separate blocks.

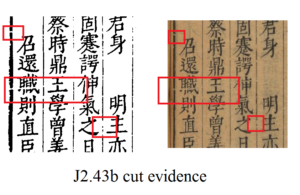

If we look at the text carefully, the term edition becomes muddy. The image below shows that the blocks in the two versions are generally the same. The cuts to the block, in the red squares, match up in both the Siku edition and the Harvard edition. A survey of the text shows that they are almost all composed of the same blocks.

But between 1605 and 1607, the text was reconceived. It went from being a finished text into a text that allowed for the inclusion of new materials. The 1605 edition begins with a table of contents after the prefaces. This table of contents lists all the memorials, as well as their classification, through the various fascicles of the book. This means that the first version was envisioned as a finished project with a set number of memorials and fascicles. In the 1607 edition, the original table of contents was discarded. Instead, each section of the work was given an independent table of contents linked to that section. At the end of each table of contents, sections of the block were left uncarved so that they could accommodate the inclusion of more texts in the future.

Above we see the familiar uncarved portion of the block. The squares in red highlight the last title of the section on “imperial reflection 修省.” The memorial in the blue, on the other hand was a new addition to the text between the 1605 and 1607 edition.

So here we see something different. As I hope this little excursion has shown, woodblocks as a printing surface were in many ways more flexible than contemporary European letterpress. Without better understanding some of these differences, the tail of European printing history will keep wagging the dog of East Asian bibliography.