You don’t often get the chance to work with woodblocks, but last week, as I was planning a class trip to the UCLA special collections to look at Manchu materials, Heather Briston, the wonderful University Archivist, and Octavio Olvera, Visual Arts Specialist, put four boxes of woodblocks onto my request. (A sign of a great librarian! I’ve been meaning to call them up, but couldn’t find them. They must have telepathically sensed my intentions.)

I’ve been thinking about blocks, and their absence in research on Chinese books, quite a bit since last year. At the Chinese books workshop I organized, Li Ren-yuan 李仁淵, at Academia Sinica, recommended that we take a look at Kaneko Takaaki’s superb Study of Early Modern Woodblocks 近世出版の板木研究. Kaneko and a team at Ritsumei have been cataloging and processing woodblocks for several years now. Their work is some of the finest research on bibliography for xylographic books that I’ve ever read (I will probably summarize it later). They’ve also built a fantastic database. I’m convinced that without a careful study of the form and variety of Chinese woodblocks, we’ll never be able to properly understand East Asian books. Unfortunately, they’re quite hard to track down.

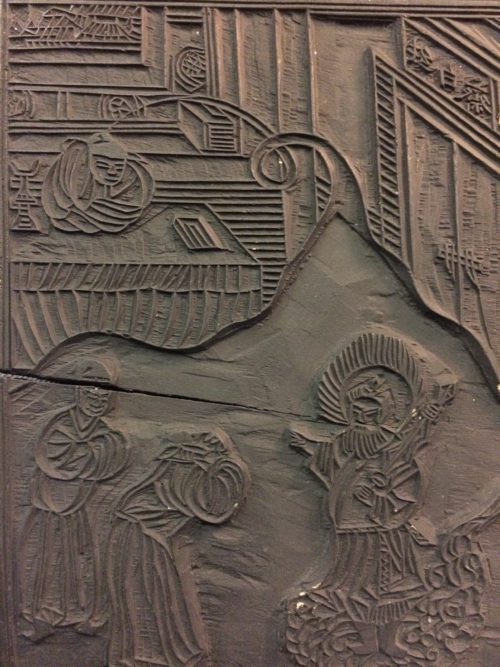

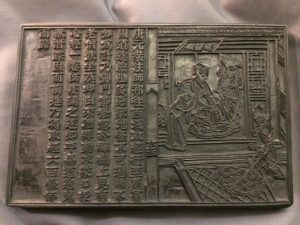

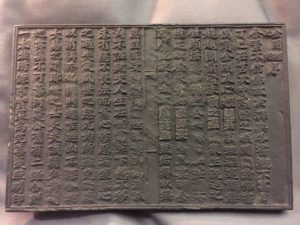

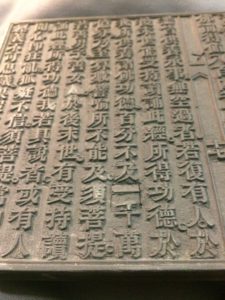

So, when Heather appeared with these boxes, preparing for the special collections visit suddenly became less important. Here they were, in inky gloriousness, almost uncatalogued, and with delightful images (all of my photographs have been reversed to make the text legible):

The blocks in question come from the Han Yushan collection, which is most famous for its examination papers, and belonged to The Diamond Sutra and the Heart Sutra, with an Appended Illustrated Explanation of Miraculous Response 金剛經心經附感應圖說, published by Zhu Xuzeng 朱續曾 in 1798. There’s allegedly a printed version somewhere in special collections, but I have not seen it yet. The blocks are all quite sturdy. It was great to pass them around to students without worrying about any damage. They’re a nice reminder of the durability of xylographic printing.

Although I’ve just started sorting through the boxes, they’ve already captured my imagination. Take a look at this image of the preface below:

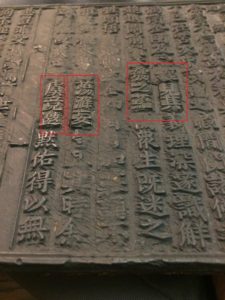

Now, you’ll probably notice that this block is badly damaged. Many of the characters have been reduced to little more than bumps on the surface. But of the 30 blocks I examined, most are still in perfect condition. More importantly, you can also see how this block was in the middle of repairs before being put away. You can see the plugs that have been inserted in the image below:

This block makes me wonder about what happened to wear it out so severly? In all likelihood, it wasn’t from printing. If it were, we would expect other blocks to show similar signs of wear. Perhaps preface wood is shaved like truffles in xylophagic cuisine.

Another repaired section of the blocks occurs on page 17, where only the character for one and the top of 1,000 (yi一, qian 千) needed mending. Aside from the preface, this is the only part of these now 220 year old blocks that needed repair. This is not to say that the blocks are in perfect condition. There are a few cracks, which would have appeared during printing. These cracks don’t render the text illegible, and I’ll hopefully discuss some aspect of them during a later post.

Oh, and if you’re curious, the blocks average 220mmx140mm, with a depth of around 15mm. Once I’ve finished cataloging them, I’ll share the complete information.