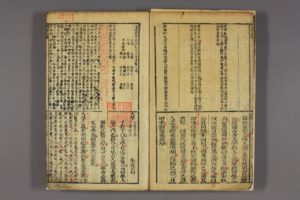

A few weeks ago, I gave a brief talk at the workshop “Asian Papers” at Dartmouth College, organized in part by my colleague and co-Mellon Fellow in Critical Bibliography, Holly Shaffer. The workshop was a welcome opportunity to start organizing some of my thoughts on the difficulty of applying Western descriptive bibliographic standards to the bibliography of the East Asian book. In line with the workshop topic, my presentation focused on the sorts of bibliographic information available from a close examination of paper.

One of the major bibliographic differences between European and East Asian paper in the early modern period is the presence of watermarks in the former. Watermarks are present in most pre-modern western paper. The earliest recorded reference to watermarks comes from the Perugia based jurist Bartolo da Sassoferrato (1314-57). He wrote:

Here there are many paper mills, and some of them produce better paper, although even here the skill of the worker is of considerable importance. And here each sheet of paper has its own watermark by which one can recognize the paper mill. Therefore, in this case the watermark should belong to the one to whom the mills itself belongs, no matter whether it remains in his possession by right of ownership or lease, or by any other title, wholly or in part, or even in bad faith. During the entire time in which he has possession of the mill, he cannot be prohibited from using the watermark…(source)

According to Sassoferrato, these watermarks allowed mills to trademark their products.

The production of watermarks is a simple process. Essentially, every piece of hand-made paper is marked with an impression of the screen which removed its wet pulp from water. Early European watermarks came from wire designs tied onto wire screens. When the screen, with the deckle on top, was dipped into a vat of pulp, the resulting paper would have the impression of both the screen wires and the design. I had a chance to see this process last year, when visiting the last wind-powered paper mill in the Netherlands, De Schoolmeester in Westzaan. (The field-trip was part of a great conference organized by Megan Williams at the University of Groningen)