In today’s post, I’ll briefly discuss late imperial fiction (xiao shuo 小說). These are very much ‘notes from the field’ based on my encounters wiht only a handful of these. I have many more questions than answers about vernacular novels.

Images

For historians of the book, one of the notable characteristics of late imperial vernacular fiction is the inclusion of images. Images were part of Chinese books from the inception of Chinese printing, but illustrated books were not nearly as common in Ming and Qing China as they were in other parts of the world.

Literary fiction, however, seems to have been illustrated from the very beginning.

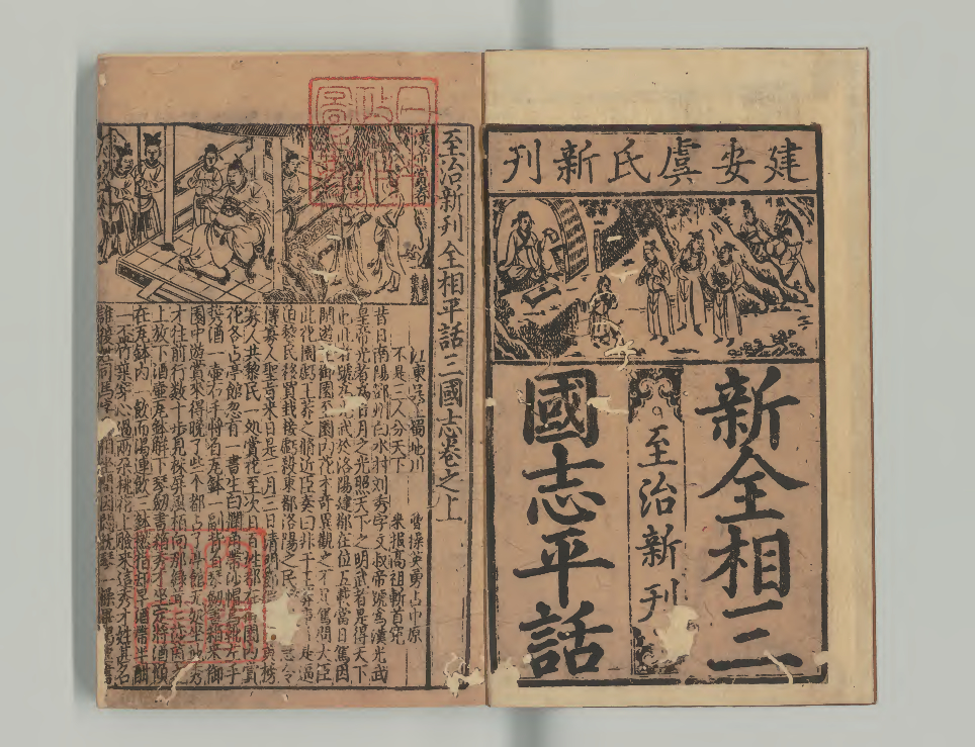

One famous example of early illustrated fiction is the image above, of the 1320s edition of the Record of the Three Kingdoms. These early printed editions were not fully mature “novels,” but were instead still closely related to the oral tradition (these were called pinghua).

Regardless of the maturity of the stories, the books themselves were already quite sophisticated market products. In the image above, the opening on the right is a full-blown title page (fengmian ye封面頁/fei ye扉頁) . The title lets us know that this is a “new engraving from the Zhizhi reign (1321-1323).” Over the iconic image on the front (which depicts Zhu Geliang in his retreat with the heroes Liu Bei, Guan Yu, and Zhang Fei asking for his aid), the name of the publisher is given: The Lu family from Jian’an (part of the Jianyang publishing center in Fujian).

The first page of the illustration is a wonderful example shang tu-xia wen 上圖下文 (image on the top and text on the bottom) format. As Robert Hegel has noted, the images often depict actions from the text, but sometimes there is no direct relationship between the scene being depicted above and the text as it exists below.

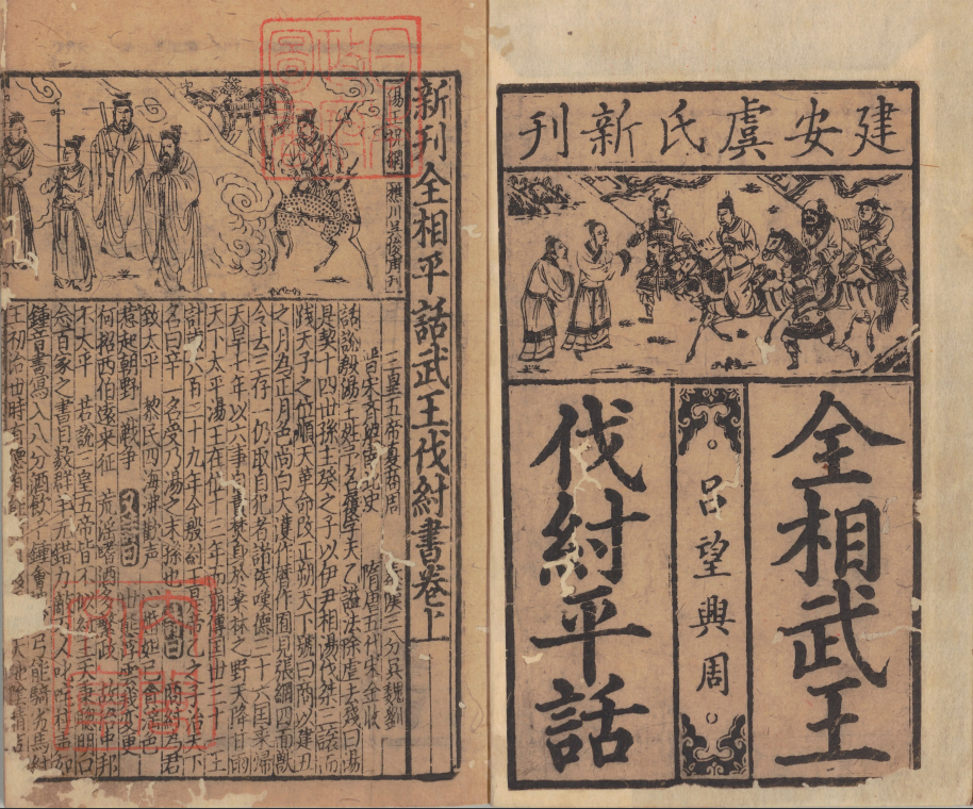

Looking at this second example from the 1320s, also printed by the Lu family, also shows us that despite literary critics’ comments of the relatively ‘under-developed’ nature of the narratives in these texts, some commercial publishers had already started to successfully brand their novel products.

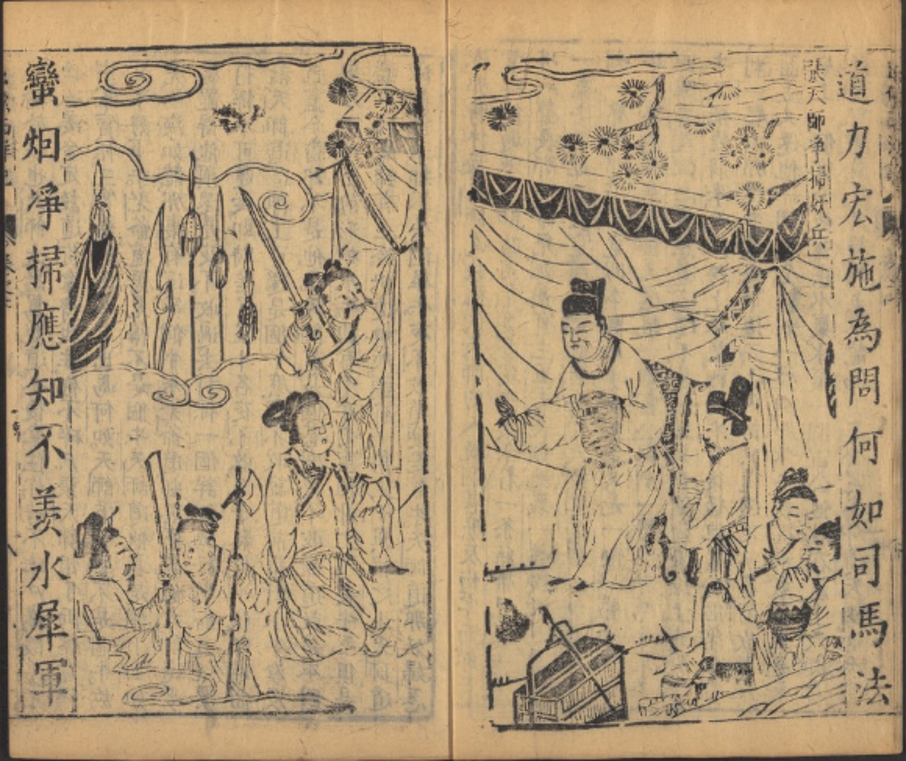

The shang tu-xia wen form of illustrated fiction remained common through the end of the Ming. In fact, they were some of the first Chinese books to arrive in Europe (see this early Oxford partial copy of Journey to the West https://iiif.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/iiif/viewer/786a9ce1-4157-4a3c-b227-c4dde74ed4cd#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=0&r=0&xywh=-2114%2C-301%2C11442%2C6013), but it was not the only format for illustrated fiction that was popular in late imperial China. This History of the Five Dynasties, 唐五代史演義傳 is another good example of a popular style of illustration. The novel begins with a series of inscribed portraits of its heroes.

https://iiif.lib.harvard.edu/manifests/view/drs:53921838$45i

Albums of characters eventually became popular on their own. Collections of images from The Outlaws of the Marsh were always popular with readers:

https://www.wdl.org/en/item/17873/#additional_subjects=Chinese+fiction

Finally, the last sort of illustrated fiction you are likely to encounter uses images at key moments during the narrative. This late Ming edition of the novel relating Zheng He’s journeys through Southeast Asia. In this novel, images come at important moments during the narrative in order to heighten the drama and the reader’s engagement.

https://iiif.lib.harvard.edu/manifests/view/drs:53924405$57i

Two activities

Now that you’ve gotten a little taste in the different roles illustration played in Chinese fiction, it’s time to try your hand at a couple of activities based around exploring digitized versions of texts.

Which one is the earlier edition?

One of the real difficulties of Chinese bibliography is trying to figure out when things are printed. As mentioned in my posts on woodblocks, determining when something was printed is often a matter of comparing multiple copies of the same work.

Both of the links below will bring you to two almost identical copies of A New Engraving of the Tale of the Eastern and Western Han 新鐫絵像東西漢全伝. To get to images of each book click on the image at the top of the page. Then, click on vol 1 – either HTML or PDF will work. Examine the books next to each other to see if you can determine which printing came first. To do this, you’ll have to really pay attention to the woodblocks – where do they break? What can the patterns of wear tell you?

Also, what model of illustrations does this novel seem to follow?

Copy 1

https://www.wul.waseda.ac.jp/kotenseki/html/he21/he21_01467/index.html

Copy 2

https://www.wul.waseda.ac.jp/kotenseki/html/he21/he21_02649/index.html

Variant Binding order and a Pirated Edition?

For this exercise, take a moment to go three these two copies of Li Zhi’s punctuated edition of Record of the Three Kingdoms.

https://www.wul.waseda.ac.jp/kotenseki/html/he21/he21_03536/index.html

https://www.wdl.org/en/item/11391/

What are the differences you notice between the locations of the images?

Compare images from the two copies – do you think these are the same edition?

Finally, compare the images from those two copies to the book below, which is a collection of images from the novel, without any text: