When I arrived at UCLA, I discovered things that bothered me. First, our historical emphasis on sixteenth century Italian printing no longer served the needs of our community of scholars and students. Second, our neglected Islamicate manuscripts were treated (if such a word can be applied to a collection that was basically neglected) as entirely separate from out collections of rare printed materials and other manuscript collections. To address these discrepancies, I began pursuing what I now refer to as ‘counter building.’ The driving idea behind counter building is that our collections should exist in dialogue or in a sort of dialectical relationship. I firmly believe that any collections of books should lead researchers to a natural process of entanglement. During the early modern period, book worlds were becoming increasingly entangled, and it should be as easy and as natural at UCLA to encounter the Islamicate as it was in 16th century Rome or Venice. Which is to say, fairly easy, even if many scholars have forgotten this.

The overall purpose of the last few years of counter building was to make it so that scholars interested in Islamicate manuscripts could, if they so desired, cross our imagined geographical boundaries from the world of Arabic, Turkish, Persian, and Urdu into print in Europe and elsewhere. As an example of how this has proceeded so far, we can consider Arabic language printing in premodern Italy. In 2021, I acquired an Italian primer to train missionaries in Arabic, printed in Rome in the 1630s. I purchased this as a way to expand our collection of Italian books and intertwine them with our existing collections. This primer was interesting for many reasons, but most appealing was the unidentified spoken Arabic used for the translation of the Lord’s Prayer. I tweeted this image out, and it immediately generated a lively discussion among linguists and Islamic studies specialists as they attempted to discern how this printed version compared to manuscript copies they knew about. One thing worth noting is that this book isn’t particularly rare, but because Western print histories never pay much attention to Arabic in print, it was unknown to its real community of researchers.

Entangling and counter building at UCLA was about more than just finding books that illustrate printing of Arabic. I tried to find copies that bring this engagement to life – albeit in the ways you would expect for someone who was trained in the Blair-Grafton school. Another book printed in Rome, the Psalms of David in Arabic, shows lively engagement with Arabic in premodern Europe. This book was acquired because its opening pages show an early European reader meticulously annotating and correcting the text. This, and other materials UCLA are small pieces of the the European engagement with the Islamicate world in both manuscript and print.

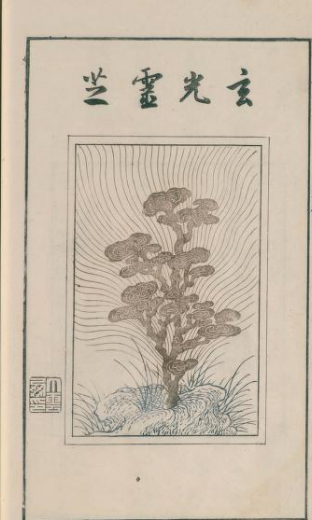

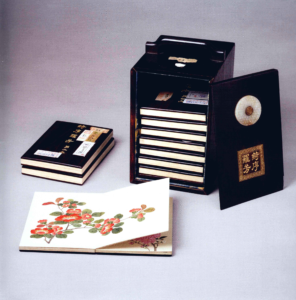

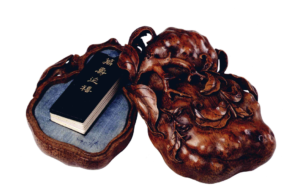

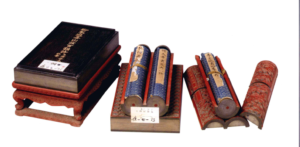

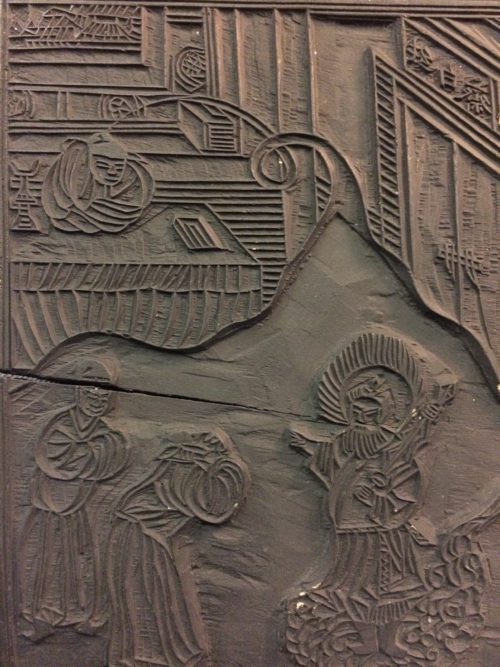

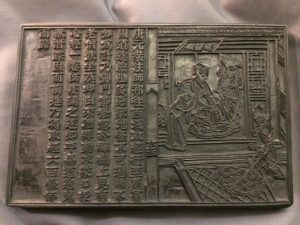

Counter building hasn’t just been a process of new acquisitions, although I spent a decent part of my annual budget on European Islamic studies. I also took to surveying existing collections for materials that expand our view of the Islamicate world. One book in the collection was a particularly exciting find. In our Chinese collection, we have a copy of the most famous Chinese-Islamic philosophical text The Metaphysics of Islam or The Philosophy of Arabia) Tian Fang Xing Li. This book was written in the 18th century by the Chinese Muslim scholar Liu Zhi. Liu read Arabic both Arabic and Persian, and had his book printed by woodblocks. On interesting fact about this book is that it was printing in Cairo at the end of the 19th century in translation as Šarḥ al-laṭā’if (شرح اللطائف) by Ma Lianyuan (馬聯元) 1841-1903.

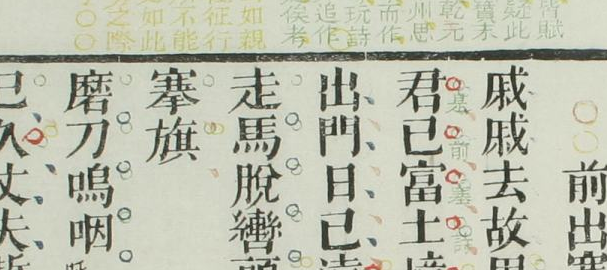

Other materials in our collection are also being used actively in teaching. The Walton Polyglot Bible, printed in London in the 1650s, was compiled by the best ‘Orientalists’ in England at the time. This book was recently used in the California Rare Books School course on the Renaissance Book as part of a broader discussion of the often-overlooked importance of Arabic knowledge in the early modern West. I also kept a volume in my office to practice languages. It’s as useful now as it has ever been!

In addition to the research returns that will come out of counter-building, there is a second way our Islamicate manuscripts effect how we are thinking about our book collections: entangling our collections of European materials with our Islamicate collections will provide greater opportunities to care for our Islamic manuscript collections. To put it rather bluntly, it is a historical fact that at UCLA (and most other places) our European studies collections have received the most support and funding of any of our bibliographical collections. This is undeniably due to the inherent Eurocentrism and structural racism of Euro-American libraries, as well as a lack of expertise. But it also has to do with how California has imagined itself.

As already noted, UCLA’s sixteenth century Italian collections are virtually unsurpassed in the United States. This occurred in part because of how UCLA saw its relationship with Southern California and its attempts to establish “Western civilization” on the West Coast. After the Huntington claimed England, we proudly claimed Italy and passively became the center for the Islamic world. Funding endowments exist for Medieval European manuscripts, but not for important Islamicate materials.

That said, I worked to blur all of these boundaries. This manuscript here is European, but it is also the only witness of the Latin translation of Abū Yūsuf Yaʻqūb ibn ʼIsḥāq aṣ-Ṣabbāḥ al-Kindī’s De unitate, De intellectu, and De somnio et visione ad imperatorum dolium. This was recently acquired for our collection – and it further part of our attempt to show that any attempts to divide Islamic and European civilization require historical forgetting. Unfortunately, UCLA forgot for decades, but over the last several years, and thanks to new efforts, we’re making things messy again.

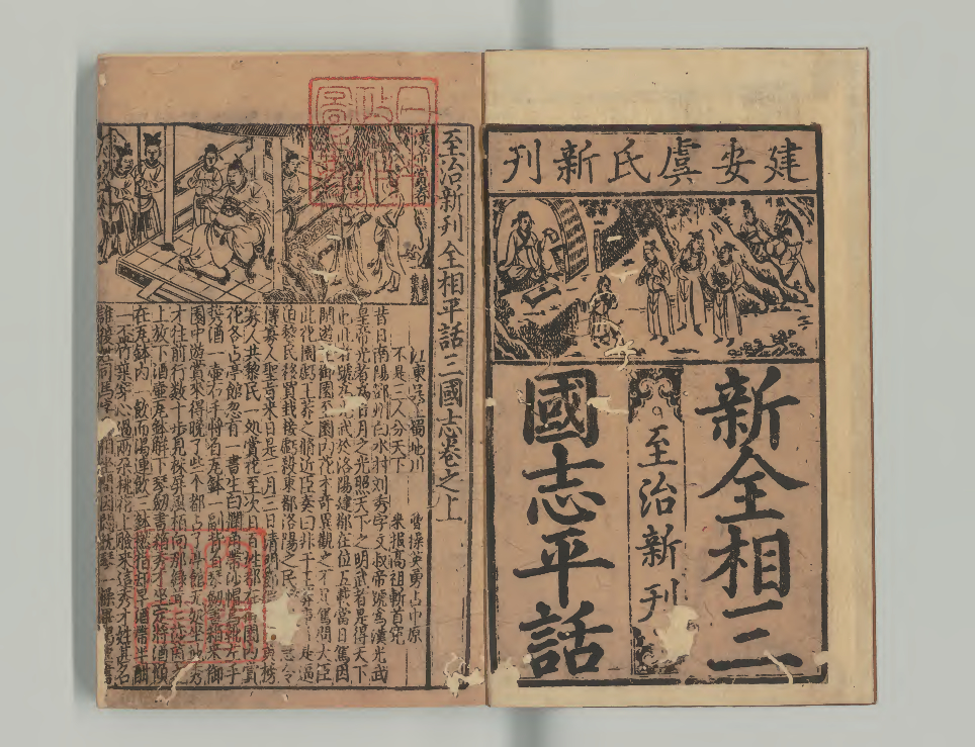

image 1: Dominicus G. Fabrica; Overo Dittionario Della Lingua Volgare Arabica Et Italiana Copioso De Voci; & Locutioni Con Osseruare La Frase Dell’ Vna & Dell’altra Lingua. Roma: Nella Stampa della Sac. Congreg. de propag. fede; 1636.

image 2: locked out of my old accounts, will get this later!

image 3: https://search.library.ucla.edu/permalink/01UCS_LAL/17p22dp/alma9913324496006531

image 4: https://search.library.ucla.edu/permalink/01UCS_LAL/17p22dp/alma997258293606533

image 5: Thomas Aquinas: Summa contra gentiles. And: Al-Kindi. De unitate, De intellectu, and De somnio et visione ad imperatorum dolium. Probably Burgundy, 1464. Signed and dated by the scribe himself (“Ego Anthonius le bysse de N. gallicus scripsique complevi hec presens opus Anno domini 1464. Vive Bourgogne”, fol. 220v).