I’ve spent the last couple of days working on a section of my dissertation describing and analyzing the famous Brevis Relatio. The story of the text is well known. In 1700, the French Jesuit Louis Le Comte and several others decided to petition the Kangxi emperor for a judicial ruling on rites to the ancestors and Confucius. On November 30, Hesishen presented a Manchu memorial to the throne outlining three key points in the Jesuit position on the rites. They stated that worship of Confucius was only to show respect to the great teachers and not “to seek wisdom or to pray for official rank or salary;” that performance of sacrifices to the dead was only so that the living will “not forget their relatives of the same clan…[and] keep them in memory forever…;” and that imperial sacrifices to Heaven were in fact “worship of Shangdi.”[Rosso, Apostolic Legations, 133-140] The emperor’s Manchu reply on the same day was brief:

This writing is very good. It accords with the great way. Respecting Heaven, serving the lord and ruler, and respecting teachers and elders are the shared precepts of the Under Heaven. So, [this memorial] is correct. There is nothing in it for emendation.

Ere arahangge umesi sain. Amba doro de acanahabi. Abka be gingulere (sic). Ejen niyaman be weilere. Sefu ungga be kundulerengge. Ere abkai fejergi uhei kooli kai. Ere uthai inu. Umai dasabure ba akū sehe.

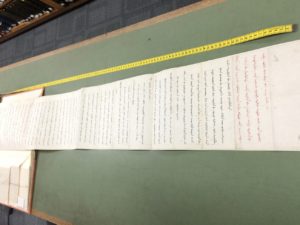

[A copy of the original Manchu, from the National Archives UK. Author’s photo]

[A copy of the original Manchu, from the National Archives UK. Author’s photo]

With the edict in hand, the Jesuits immediately prepared letters to send to Europe with copies of the original Manchu documents, Latin translations of the text, and brief explanations of its significance. The packet sent to the French Jesuit Charles Le Gobien included a personal letter from Antoine Thomas promising that in the next year he would send the learned opinions of Chinese scholars to support the emperor’s decision. When the letter to the pope arrived in Rome, the Latin translation of the edict was apparently published alongside an Italian vernacular (now lost). Soon after, an edition in Liege published a French translation alongside the Latin prepared in Beijing .

The next year, in 1701, Thomas’ promise for more testimony was fulfilled, and another version of the edict was prepared in Beijing to be sent to Euope. The more significant published work for publicly outlining Jesuit-Qing positions on the rites was the famous Brevis Relatio. The Jesuits, with the emperor’s approval, used court block-carvers and printers to produce a xylographic print some one-hundred and thirty pages in length. The print included the details from the original letters in 1700, including the Manchu memorial (without the Manchu rescript), the Chinese version of the edict as it circulated in Qing gazettes, Qing testimonies on the correctness of Jesuit interpretations, quotations from classical sources, and some detailed discussions of key events and terms, such as the tiantian (the altar of Heaven). The 1701 version of the text was sent off to Europe along four different routes. In Europe, it appeared in several different editions.

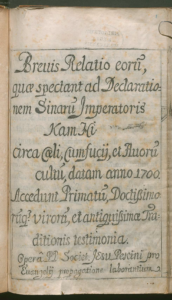

[Copy of the Beijing edition from the Bavarian State Library]

[Copy of the Beijing edition from the Bavarian State Library]

The fun, for me at least, has been thinking about how the Manchu, Chinese, French, Latin, English, and Dutch versions of the edict compare to one another. Particularly interesting is the transformation of “Under Heaven” to world, orbi, monde, etc. Also of interest is the difference between tongyi 通義 in Chinese, the Manchu kooli, and the different sense of law in the European translations.

Ce qui est contenu dans cet Ecrit est tres-bien, & tres-conforme à la grande Doctrine. Rendres ses devoirs au Ciel, à ses Seigneurs, à ses Parents, à ses Maitrers & à Ses Ancestres, c’est une loy commune à tout le monde. Les choses, qui sont continues dans cets ecrit sont tres vrayesm & il n’y a rien à coriger.

Quae in hoc scripto continentur, optimè scripta sunt, et plane que concordant cum magnâ doctrinà. Caelo, Dominis, Parentibus, Magistrics ac Proavis debita obsequie paestare, ista universe Orbi communis lex est. Ea quae in hoc scriptio continentur, sunt versissima, neque egent ullâ prorsùs emendation

The Contents of this Writing are well Written, and agree perfectly with the great Doctrine. All Nations in the World lie under an obligation of paying due respect to Heaven, their Rulers, Parents, Masters, and Ancestors. The Contents of this Paper are exactly true and want no corrections at all.

Dese dingen, die in dit Schrift, vervat worden, syn seer wel geschreven, en komen gantschelyk over een met de Groote Leeringe. Den Hemel, de Heeren, Ouders, Meesters, en Voorouders, schuldige Gedientigheyd te bewysen, dat is een Wet, die de gantsche Weereld gemeen is. De Dingen, die in die Schrift vervat worden, syn seer Waaragtig, ende en hebben in’t geheel geen Verbeteringe van node.

這所寫甚好有合大道敬天及事君親敬師長者系天下通義就是無可改處

Ere arahangge umesi sain. Amba doro de acanahabi. Abka be gingulere. Ejen niyaman be weilere. Sefu ungga be kundulerengge. Ere abkai fejergi uhei kooli kai. Ere uthai inu. Umai dasabure be akū sehe.

I talk more about much of this in my dissertation, but I probably won’t be able to put all of these versions next to each other (maybe one of the 10,000 appendixes I’m working on). So, to the blog with them!