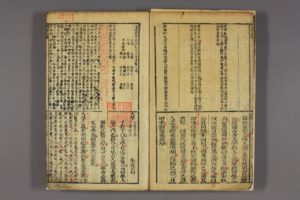

Things you can do with Woodblocks (1)

Welcome to a new series entitled, “Things you can do with woodblocks.” The purpose of this series is to begin outlining some of the special features of xylographic printing with useful visuals.

Black blocks

Until the 19th century invention of different forms of plate printing (stereotype, elecotrotype), it was rather difficult to keep type “standing.” ABCs for Book Collectors explains ‘standing type’ to mean:

The type from which a book was printed was not always distributed immediately after use. It was sometimes kept and used for a subsequent impression, which is then said to be printed from standing type. (209)

Printers only kept standing type in rare circumstances. For most jobs, when printing was done, type would be redistributed to type-cases to wait for the next project.

Xylographically printed books, on the other hand, lasted far longer. If blocks were properly cared for, you could use them for a few generations (with occasional repairs). This also meant that the same blocks could be used for new ‘editions.’ (Edition is a problematic concept in this case, but we’ll talk about this later) Continue reading “Things you can do with Woodblocks (1)”