In this post, inspired by a fun twitter thread by Shannon Supple, Curator of Rare Books at Smith College, on annotation (so many month ago now!), I’m going to introduce some of the basic features of textual annotation/punctuation – sometimes called judou 句讀 (reading marks) or pidian 批點 (comment marks) – in Chinese printed books.1

I first learned classical Chinese with Alvin P. Cohen at UMass, Amherst. This had some influence on my undergraduate social life, because Dr. Cohen, like many a hard-nosed philologist before him, believed in teaching unpunctuated classical Chinese. I spent countless hours before each 50 minute class trying to punctuate texts, look up characters, and pretend I had the faintest idea of what was happening. My notes from those days show it was not a pretty sight. (I’ll add a photo when I am back stateside.)

Because texts without punctuation can be a pain, people began punctuating Chinese early in its history. Consider this 7th century colophon to the Lotus Sutra found by Imre Galambos:

I punctuated this sūtra for beginner students who read it but are unfamiliar with the segmentation of the text. I neither paid attention to larger sections, nor considered their beginning and end. For the most part segments consist of four characters and I started punctuating them when the segments did not comprise four characters. But for four-character segments I added no dots whatsoever….In this manner, I tentatively distinguished them. Let those who see this later not blame me for using red marks and say that the punctuation is flawed. 余為初學讀此經者不識文句,故憑點之。亦不看科段,亦不論起盡,多以四字為句,若有四字外句 者,然始點之;但是四字句者,絕不加點。別為作為(帷委反);別行作行(閑更反)。如此之流,聊 復分別。後之見者,勿怪下朱,言錯點也。2

This colophon tells us two things that are comforting. First, it tells us that the punctuator inserted his dots and dashes into the text to help novices (Dr. Cohen was cruel even by 7th century standards!). Secondly, he apologized for inevitably getting the punctuation wrong. That second point is a good reminder that punctuating texts was/is hard. As one of my advanced students in a Qing documents class at UCLA noted last fall, she only ‘finally’ started to get the feel for unpunctuated texts after I exiled her to special collections for several hours of uninterrupted reading.

By the time the Ming (1368-1644) rolled around, punctuation in printed materials, particularly popular texts, was fairly common. But how to punctuate?

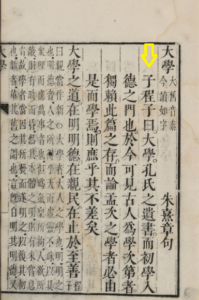

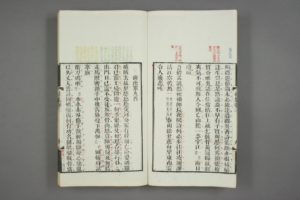

In general, there are two forms of punctuation you’re likely to encounter in a printed book: ‘grammatical’ and/or ‘commentarial.’ This distinction, which I’ve just made up, will be clear if we look at two examples. The first, from a Ming edition of Zhu Xi’s commentary on the Four Books has ‘grammatical punctuation.’ This punctuation (and I’ll ask linguists to explain its history on my behalf!) breaks Chinese sentences into grammatical units that my intuition labels as one of three things: 1: ‘topic.’ 2: ‘comment.’ or a 3: ‘topic-comment.’ By chunking the text into smaller logical units, readers are saved from a great deal of head-scratching.[N. It is important to remember that almost every Chinese word can be used as a verb.]

Here is what this looks like with part of the text translated into English. The red circles reflect the black circles in the Chinese text:

Master Cheng said 0 The Great Learning (topic)0 is a book left by Confucius (comment) 0 and a primer to entering the gateway of virtue (comment)0 What we can observe about the progress of the studies of the ancients in the present 0 depends entirely on the preservation of this text 0

Sishu ji zhu, Zhu Xi commentary四書集註 : 21卷 / 朱熹集註章句.(16th century?), 1a.

(Click on the image for a larger size)

Looking at the work of the Chinese punctuation leaves little doubt about its utility. If the dots were not there, it would be possible to come up with several alternative readings.

But what about ‘commentarial’ punctuation marks? Generally speaking, there were slight variations between different genres of texts and the meaning of commentarial punctuation. Both Timothy Clifford and Hilde De Weerdt have translated different examples, and they are both worth consulting if you are interested.3 Histories, for example, often have special punctuation marks for place names or personal names. Literary punctuation often emphasized style or rhetorical value.

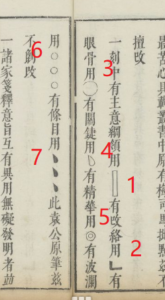

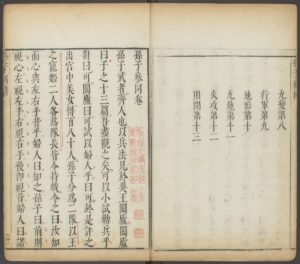

To get a sense of how this worked, we’ll briefly look at punctuation from from a commentary of Sun Zi’s Art of War 孫子參同

In the carving, those sections which are essential to the primary meaning of the text are marked with (1); those which change the sticking point use (2); places which are forceful use (3); place which are essential use (4); place which are elegant use (5); places with wave-like rhythm use (6); and place which enumerate use (7)…

Sunzi Can tong, 孫子參同五卷. 明萬曆庚申 (1620), fanli.

The above forms of punctuation help the reader to know when they should be paying careful attention to the important sections of the text and also signal transitions in topic. Moreover, the later sets of punctuation also indicate that parts of the work had important aesthetic features for readers to learn from.

Turning to the text, we see how this punctuation breaks up the page and pulls readers’ attention between different lines. Even without knowing Chinese, your eye naturally drifts to highlighted sections.

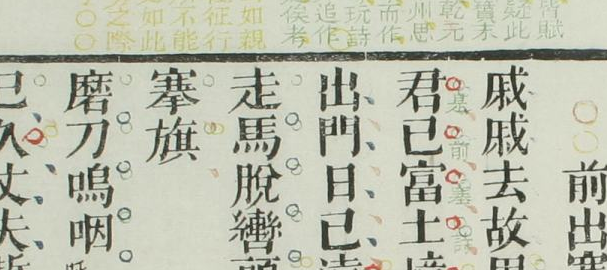

The final example to consider is a text that has both forms of punctuation as well as printed marginalia (marginalia will get its own post at some point). In this late Qing collection of Du Fu’s (D. 770) poems, layers of different commentary and punctuation were reproduced in the text (which would have taken 6 different blocks to produce). In the example page below, we can see how the layering of 5 different commentaries and readers’ punctuation over a page marked up the text using some familiar forms of punctuation. It’s a good image to end on, since it raises more questions than a single blog post can hope to answer. Also, it’s quite nice to look at:

Du gong bu ji: Wu jia ben杜工部集 : 五家本., comp Wang Shizhen. (Guangxu ed.?), j3. 9b-10a.

I’m ending this blog also with a big thank you to Timothy Clifford, who knows more about this than I could ever hope to. And also to Shannon Supple for making sure Chinese books get a place in her teaching!

- A good starting point for learning about this is: David L. Rolston, Traditional Chinese Fiction and Fiction Commentary: Reading and Writing Between the Lines (Stanford University Press, 1997) ↩

- Imre Galambos, “Punctuation Marks in Medieval Chinese Manuscripts,” in Manuscript Cultures: Mapping the Field, ed. Jan-Ulrich Sobisch, Dmitry Bondarev, and Jörg Quenzer (De Gruyter, 2014), 352. ↩

- Hilde De Weerdt, “The Construction of Examination Standards: Daoxue and Southern Song Dynasty Examination Culture” (Ph.D. Dissertation, Harvard University, 1998), pages 192-93. Timothy Clifford, “The Rules of Prose in Sixteenth-Century China: Tang Shunzhi (1507-1560) as an Anthologist,” draft paper.Tim very generously shared his paper with me, and also provided the reference to De Weerdt’s translation. Keep your eyes peeled for this article! ↩